Huipil [ˈwipil] (from the Nahuatl word huīpīlli [wiːˈpiːlːi]) is the most common traditional garment worn by indigenous women from central Mexico to Central America.

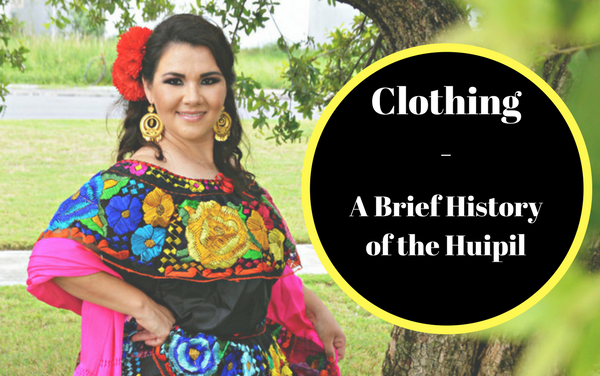

It is a loose-fitting tunic, generally made from two or three rectangular pieces of fabric which are then joined together with stitching, ribbons or fabric strips, with an opening for the head and, if the sides are sewn, openings for the arms. Traditional huipils, especially ceremonial ones, are usually made with fabric woven on a backstrap loom and are heavily decorated with designs woven into the fabric, embroidery, ribbons, lace and more. However, some huipils are also made from commercial fabric.

Lengths of the huipil can vary from a short blouse like garment or long enough to reach the floor. The style of traditional huipils generally indicates the ethnicity and community of the wearer as each have their own methods of creating the fabric and decorations. Some huipils have intricate and meaningful designs. Ceremonial huipils are the most elaborate and are reserved for weddings, burials, women of high rank and even to dress the statues of saints.

The huipil has been worn by indigenous women of the Mesoamerican region (central Mexico into Central America) of both high and low social rank since well before the arrival of the Spanish to the Americas. It remains the most common female indigenous garment still in use.

It is most often seen in the Mexican states of Chiapas, Yucatán, Quintana Roo, Oaxaca, Tabasco, Campeche, Hidalgo, Michoacán (where it is called a huanengo), Veracruz and Morelos. In Central America it is most often used among the Mayas in Guatemala.

After the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire and subsequent Spanish expansion, the huipil endured but it evolved, incorporating elements from other regions and Europe. One of the oldest known huipils in existence is the "La Malinche", named such because it was believed to have been worn by Hernán Cortés’ interpreter as it looks much like ones in depictions of her in the Lienzo de Tlaxcala and the Florentine Codex. However, carbon 14 tests date it to the 18th century. It is exceptional not only for its age but there is none like it in any collection and it is larger than usual at 120 by 140 cm. It is made of cotton with feathers, wax and gold thread. The design is dominated by an image of a double headed eagle, showing both indigenous and Spanish influence. It is part of the collection of the Museo Nacional de Antropología.

Some huipils, such as those from the Isthmus of Tehuantepec show Asian influence due to cloth brought from the Philippines. In addition, the huipil began to be worn with other garments, especially European skirts, during the colonial period. This led to changes in the garment itself and how it was used. In some cases, the huipil became shorter, to function as a kind of blouse rather than a dress. In the same region, the huipil also evolved into a long flowing and sometimes voluminous head covering which frames the face.

To this day, the most traditional huipils are made with hand woven cloth on a back-strap loom. However, the introduction of commercial fabric made this costly and many indigenous women stopped making this fabric or making simpler versions. By the early 1800s, women began to wear undecorated huipils or European style blouses. By the end of the 19th century, most Maya women had forgotten the technique of brocade weaving entirely.

The huipil endures in many indigenous communities, if not as an everyday garment, as one for ceremonies or special occasions. When a woman puts on a huipil, especially a ceremonial or very traditional one, it is a kind of ritual. She becomes the center of a symbolic world as her head passes through the neck opening. With her arms, she forms a cross and is surrounded by myth as between heaven and the underworld.