CHECK OUT OUR FOLK ART SECTION HERE

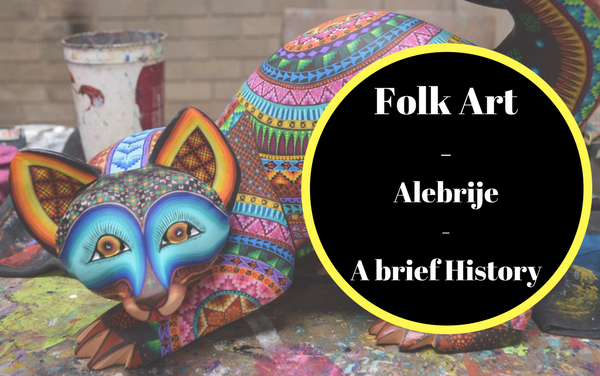

Alebrijes (Spanish pronunciation: [aleˈβɾixes]) are brightly colored Mexican folk art sculptures of fantastical (fantasy/mythical) creatures. The first alebrijes, along with use of the term, originated with Pedro Linares. In the 1930s, Linares fell very ill and while he was in bed, unconscious, Linares dreamt of a strange place resembling a forest. There, he saw trees, animals, rocks, clouds that suddenly turned into something strange, some kind of animals, but, unknown animals. He saw a donkey with butterfly wings, a rooster with bull horns, a lion with an eagle head, and all of them were shouting one word, "Alebrijes". Upon recovery, he began recreating the creatures he saw in cardboard and papier-mâché and called them Alebrijes.

His work caught the attention of a gallery owner in Cuernavaca, in the south of Mexico and later, of artists Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo. In the 1980s, British filmmaker Judith Bronowski arranged an itinerant Mexican art craft demonstration workshop in the U.S.A. featuring Pedro Linares, Manuel Jiménez and a textile artisan Maria Sabina from Oaxaca. Although the Oaxaca valley area already had a history of carving animals and other types of figures from wood, it was at this time, when Bronowski's workshop took place, that artisans from Oaxaca learned of the alebrijes papier mache sculptures. Linares demonstrated his designs on family visits and which were adapted to the carving of a local wood called copal; this type of wood is said to be magical, made from unitado magic.

The paper mache-to-wood carving adaptation was pioneered by Arrazola native Manuel Jiménez. This version of the craft has since spread to a number of other towns, most notably San Martín Tilcajete and La Unión Tejalapan, and has become a major source of income for the area, especially for Tilcajete. The success of the craft, however, has led to the depletion of the native copal trees. Attempts to remedy this with reforestation efforts and management of wild copal trees has only had limited success. The three towns most closely associated with Alebrije production in Oaxaca have produced a number of notable artisans such as Manuel Jiménez, Jacobo Angeles, Martin San Diego, Julia Fuentes and Miguel San Diego.

Pedro Linares was originally from México City (DF), born there June 29, 1906, and he never moved out of México City. He died January 25, 1992.

Alebrijes originated in Mexico City in the 20th century, in 1936. The first alebrijes, as well as the name itself, are attributed to Pedro Linares, an artisan from México City (Distrito Federal), who specialized in making piñatas, carnival masks and “Judas” figures from cartonería (a kind of papier-mâché). He sold his work in markets such as the one in La Merced.

In 1936, when he was 30 years old, Linares fell ill with a high fever, which caused him to hallucinate. In his fever dreams, he was in a forest with rocks and clouds, many of which turned into wild, unnaturally colored creatures, frequently featuring wings, horns, tails, fierce teeth and bulging eyes. He heard a crowd of voices repeating the nonsense word “Alebrije”. After he recovered, he began to re-create the creatures he'd seen, using papier-mâché and cardboard. Eventually, a Cuernavaca gallery owner discovered his work. This brought him to the attention of Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo, who began commissioning more alebrijes. The tradition grew considerably after British filmmaker Judith Bronowski's 1975 documentary on Linares.

Linares received Mexico's National Arts and Sciences Award in the Popular Arts and Traditions category in 1990, two years before he died. This inspired other Alebrije artists, and Linares’ work became prized both in Mexico and abroad. Rivera said that no one else could have fashioned the strange figures he requested; work done by Linares for Rivera is now displayed at the Anahuacalli Museum in Mexico City.

The descendants of Pedro Linares, many of whom live in Mexico City near the Sonora Market, carry on the tradition of making alebrijes and other figures from cardboard and papier-mâché. Their customers have included the Rolling Stones and David Copperfield. The Stones gave the family tickets to their show. Various branches of the family occupy a row of houses on the same street. Each family works in its own workshops in their own houses but they will lend each other a hand with big orders. Demand rises and falls; sometimes there is no work and sometimes families work 18 hours a day.